What is

Leukemia:

From

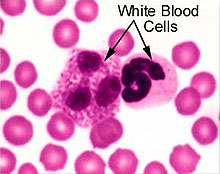

the Greek meaning "white blood". Leukemia is a

cancer of a

marrow cell. The term refers to a group of closely related malignant conditions

affecting the immature blood-forming cells in the bone marrow. so is that

certain cells in the body become abnormal. Another is that the body keeps

producing large numbers of white cells. From

the Greek meaning "white blood". Leukemia is a

cancer of a

marrow cell. The term refers to a group of closely related malignant conditions

affecting the immature blood-forming cells in the bone marrow. so is that

certain cells in the body become abnormal. Another is that the body keeps

producing large numbers of white cells.

Under normal circumstances, cells are formed, mature, carry out their function,

and die. New cells are constantly being formed to take their places. Normal

blood contains 3 major groups of cells: white blood cells, red blood cells, and

platelets. All 3 types develop from one immature cell type called stem cells in

a process called hematopoiesis.

|

In humans, the bones are not

solid, but are made up of two distinct regions. The outer,

weight-bearing area is hard, compact, and calcium-based. It surrounds a

lattice-work of fibrous bone known as cancellous tissue. The inner

region, or marrow - which is one of the largest organs of the body - is

located within the bones.

The marrow may contain fat cells,

fluid, fibrous tissue, blood vessels, and hematopoietic, or blood-forming,

cells. Marrow looks yellow when it holds many fat cells; it appears red when

it has more blood-forming material. The marrow is the principal site for

hematopoiesis (blood formation), which, after birth, occurs primarily within

the bones of the legs, arms, ribs, sternum (breastbone), and vertebrae

(backbones).

|

Leukemia occurs when immature or mature

cells multiply in an uncontrolled manner in the bone marrow. It is classified as

lymphocytic or myeloid, according to the type of cell that is multiplying

abnormally, and either acute, signifying rapidly progressing disease with a

predominance of highly immature (blastic) cells, or chronic, which denotes

slowly progressing disease with greater numbers of more mature cells

What Causes Leukemia:

The exact cause of most cases of

leukemia is not known. But doctors have found that this cancer is linked to a

number of risk factors.

-

Smoking

is considered a risk factor for leukemia, as for other cancers, but many

people who have leukemia never smoked, and many people who smoke never get

leukemia. Potential leukemia-causing chemicals in tobacco smoke include

benzene, polonium-210, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). These

carcinogens (cancer-causing substances) are absorbed by the lungs and are

spread via the bloodstream. It is estimated that one in four cases of

acute myelogenous leukemia (AML)

is the result of cigarette smoking. Smoking

is considered a risk factor for leukemia, as for other cancers, but many

people who have leukemia never smoked, and many people who smoke never get

leukemia. Potential leukemia-causing chemicals in tobacco smoke include

benzene, polonium-210, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). These

carcinogens (cancer-causing substances) are absorbed by the lungs and are

spread via the bloodstream. It is estimated that one in four cases of

acute myelogenous leukemia (AML)

is the result of cigarette smoking.

-

Long-term exposure to chemicals such as benzene or formaldehyde, typically

in the workplace, is considered a risk factor for leukemia, but this

accounts for relatively few cases of the disease.

-

Exposure to extraordinarily high

doses of radiation is a risk factor, although this accounts for

relatively few cases of leukemia. It is important to note, however, that

standard diagnostic X-rays pose little or no increase in leukemia risk.

Other risk factors for leukemia

include the following:

-

Previous

chemotherapy: Drugs called alkylating agents used to treatment certain

types of cancers are linked to development of leukemia later.

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) has been reported after chemotherapy

and/or radiotherapy for various solid tumors (breast

cancer,

ovarian cancer),

blood malignancies, and nonmalignant conditions. The chemotherapeutic agents

most often associated with secondary leukemias are procarbazine,

chlorambucil, etoposide, mechlorethamine, teniposide, and cyclophosphamide.

The risk is increased when these drugs are combined with radiation therapy.

-

Human T-cell leukemia virus 1

(HTLV-1): Infection with this virus is linked to human T-cell leukemia.

Excess leukemias also have been reported in workers who are exposed to

animal viruses - for example, butchers, slaughterhouse workers, and

veterinary practitioners.

-

Myelodysplastic syndrome: This blood disorder increases the risk of acute

myelogenous leukemia.

-

Down

syndrome and other genetic diseases: Leukemia risk is increased 15-fold

among children with Down's syndrome, which is a genetically linked

chromosomal abnormality (usually an extra copy of chromosome 21). Three rare

inherited disorders - Fanconi's anemia, Bloom's syndrome, and ataxia

telangiectasia - also have a greatly increased risk of leukemia. In

addition, leukemia varies among racial and ethnic groups with different

genetic make-ups. Down

syndrome and other genetic diseases: Leukemia risk is increased 15-fold

among children with Down's syndrome, which is a genetically linked

chromosomal abnormality (usually an extra copy of chromosome 21). Three rare

inherited disorders - Fanconi's anemia, Bloom's syndrome, and ataxia

telangiectasia - also have a greatly increased risk of leukemia. In

addition, leukemia varies among racial and ethnic groups with different

genetic make-ups.

-

Family history: Having a

first-degree relative who has chronic lymphocytic leukemia increases your

risk of having the disease by as much as 4 times that of someone who does

not have an affected relative.

-

Age - Roughly 60% to 70% of leukemias occur in people who are older

than 50.

Translocations are another type of DNA problem that can lead to leukemia.

Human DNA is packaged in 23 pairs of chromosomes. If DNA from one chromosome

gets attached to the wrong chromosome, cancer can result.

Types of Leukemia:

Bone

marrow, the material filling the body's bones, is the adult source of the body's

blood cells and produces two blood cell lines, the myeloid and the

lymphoid. Bone

marrow, the material filling the body's bones, is the adult source of the body's

blood cells and produces two blood cell lines, the myeloid and the

lymphoid.

Myeloid Cell Line. The myeloid cell line includes early cells that

mature into red

blood cells, blood clotting agents (platelets), and some white blood

cells. These white blood cells include

macrophages,

eosinophils, and

neutrophils.

Lymphoid Cell Line. The lymphoid cell line includes two of the

body's primary infection fighters known as T-cell and B-cell

lymphocytes

. Part of their role is to produce antibodies, factors that can target and

attack specific foreign agents (antigens) in the body.

Depending on the types of cell the

disease appears in one of four major forms:

-

Acute

lymphocytic leukemia- Acute lymphocytic leukemia, also called

acute lymphoblastic leukemia and acute lymphoid leukemia, is a common

leukemia. About 4,000 new cases are diagnosed each year in the United

States. Most cases of acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) occur in children

under age 10, but it can appear in all age groups. ALL is an acute leukemia,

which means it is a disease that gets worse quickly. Acute

lymphocytic leukemia- Acute lymphocytic leukemia, also called

acute lymphoblastic leukemia and acute lymphoid leukemia, is a common

leukemia. About 4,000 new cases are diagnosed each year in the United

States. Most cases of acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) occur in children

under age 10, but it can appear in all age groups. ALL is an acute leukemia,

which means it is a disease that gets worse quickly.

-

Acute myelogenous leukemia characterized by the

uncontrolled proliferation and accumulation of abnormal immature cells,

referred to as leukemic blasts. These cells fill the marrow spaces and enter

the blood.

-

Chronic myelogenous leukemia - Chronic myelogenous

leukemia (CML) is a myeloproliferative disorder characterized by increased

proliferation of the granulocytic cell line without the loss of their

capacity to differentiate, and

-

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia are less rapidly

progressive.

The former, however, requires treatment

in nearly all cases at the time of diagnosis, whereas the later may, in some

cases, be non-progressive for long periods

Symptoms of Leukemia:

Broad

symptoms of leukemia may include:

-

Fatigue Fatigue

-

Malaise (vague feeling of bodily

discomfort)

-

Abnormal bleeding

-

Excessive bruising

-

Weakness

-

Reduced exercise tolerance

-

Weight loss

-

Bone or joint pain

-

Infection and fever

-

Abdominal pain or "fullness"

-

Enlarged spleen, lymph nodes, and

liver

-

Chronic leukemia often goes undetected

for many years until it is identified in a routine blood test. In fact,

nearly one in five chronic leukemia patients have no symptoms at the time of

their diagnosis. Most symptoms of acute leukemia are caused by a lack of

normal blood cells. This is due to overcrowding of the blood-forming bone

marrow by leukemia cells.

Signs of Blood Abnormalities

Once the patient's blood is tested, signs of specific blood abnormalities may be

noted, such as:

-

Anemia - a low number of erythrocytes (red blood cells) within the

blood. Anemia can cause fatigue, "pale" skin coloration, and respiratory

difficulties such as shortness of breath.

-

Leukopenia - a low number of normal

leukocytes (white blood cells) that may increase the risk of infection. A

reduction in WBC count is also encountered with toxemia and septicemia.

-

Neutropenia (granulocytopenia) - too

few mature neutrophils, the mature bacteria-destroying white blood cells

that contain small particles, or granules.

-

Thrombocytopenia - a low number of

blood-clotting platelets that can result in excessive bruising, abnormal

bleeding, or frequent bleeding of the nose or gums.

-

Thrombocytosis - a high number of

platelets. Some patients, especially those with chronic myelogenous leukemia

(CML), may exhibit thrombocytosis, although their platelets may not clot

properly, causing bruising and bleeding difficulties.

-

Because

leukemia may cause enlarged spleen (splenomegaly) and enlarged liver

hepatomegaly (enlarged liver), the overgrowth of these organs may appear as

belly "fullness" or swelling. Such fullness may be palpated (felt) by the

physician during physical examination. Lymph node enlargement may or may not

be apparent, although imaging studies should be able to confirm any

lymphatic disease. Because

leukemia may cause enlarged spleen (splenomegaly) and enlarged liver

hepatomegaly (enlarged liver), the overgrowth of these organs may appear as

belly "fullness" or swelling. Such fullness may be palpated (felt) by the

physician during physical examination. Lymph node enlargement may or may not

be apparent, although imaging studies should be able to confirm any

lymphatic disease.

-

Leukemia that has spread to the brain

may produce central nervous system effects, such as headaches, seizures,

weakness, blurred vision, balance difficulties, or vomiting.

Certain forms of leukemia produce more

distinct symptoms. For example,

acute myelogenous leukemia (AML),

particularly the M5 monocytic form, may generate tell-tale symptoms such as:

-

swollen, painful, and bleeding gums -

if AML has spread to the oral tissue;

-

pigmented (colored) rash-like spots -

if AML has spread to the skin; or

-

chloromas - if AML has spread to the skin or other organs.

The T-cell variety of

acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL)

may cause the thymus to enlarge and press on the trachea (windpipe). Such

pressure may lead to:

-

shortness of breath,

-

coughing, or

-

suffocation.

If the overgrown thymus presses upon the

superior vena cava (SVC), the large vein that carries blood from the head and

arms back to the heart, this may produce

SVC syndrome. SVC involvement of the brain can be fatal.

Diagnosis of Leukemia:

The following methods may be used to

diagnose leukemia:

-

The signs and symptoms may suggest a

diagnosis of leukaemia. On examination there may be enlarged lymph glands,

hepatomegaly and/or

splenomegaly.

-

A urine sample is checked for blood.

-

Blood tests such as a full blood count

will check the number of each type of white blood cell in the sample. It will

indicate the presence of anaemia or a reduction in the number of platelets.

-

A blood film is done to check the

appearance of the blood cells. This involves taking a very small amount of blood

from the sample and smearing it on a slide, which is then viewed under a

microscope. Immature or abnormal blood cells can be seen on the slide.

-

Bone

marrow biopsy involves the removal of some bone and marrow from the sternum or

the hipbone. This is usually done under local anaesthetic, although in small

children general anaesthetic may be required. The sample of bone marrow is

spread on a slide and examined under a microscope. Bone

marrow biopsy involves the removal of some bone and marrow from the sternum or

the hipbone. This is usually done under local anaesthetic, although in small

children general anaesthetic may be required. The sample of bone marrow is

spread on a slide and examined under a microscope.

A beam of light (usually laser light) of a single frequency (colour) is directed

onto a hydrodynamically focused stream of fluid. A pair of detectors are aimed

at the point where the stream passes through the light beam; one in line with

the light beam and one perpendicular to it. Each suspended particle passing

through the beam scatters the light in some way, and chemicals in the particle

may be excited into emitting light at a lower frequency than the light source.

This combination of scattered and fluorescent light is picked up by the two

detectors, and by analyzing fluctuations in brightness and frequency at each

detector it is possible to deduce various facts about the physical and chemical

structure of each individual particle.

Treatment of Leukemia:

Chemotherapy,

radiotherapy and bone marrow transplant (BMT) are used to treat

leukaemia. There are different types of chemotherapy (called protocols) each

involving a number of anticancer drugs given at the same time. Chemotherapy,

radiotherapy and bone marrow transplant (BMT) are used to treat

leukaemia. There are different types of chemotherapy (called protocols) each

involving a number of anticancer drugs given at the same time.

The effectiveness of treatment for

leukaemia depends on the type and stage of the disease. Acute leukaemia often

goes into

remission. However, many people with acute leukaemia have a relapse (the

disease returns).

Chronic leukaemias develop more slowly than the acute types, but respond less

well to chemotherapy and are rarely cured.

Acute leukaemia

Acute leukaemia is treated with

chemotherapy to destroy the abnormal cancer cells. Mixtures of drugs are given

into a vein in a series of treatment courses.

Medicines are available which reduce the

side-effects of chemotherapy such as nausea. Hair may fall out during treatment

but it re-grows once the chemotherapy has stopped. Some people may be able to

use "cold caps" which cool the scalp and help prevent hair loss.

If the leukaemia returns (relapses),

intensive treatment may be given. This involves a bone marrow or a stem cell

transplant. Bone marrow or stem cell transplants allow much higher doses of

chemotherapy to be given.

Before transplantation, very high doses

of chemotherapy and sometimes radiotherapy are given to destroy all the bone

marrow, both abnormal and normal. This improves the chance of completely curing

the leukaemia.

Then normal bone marrow cells, donated

from a close relative or carefully removed from the person's own bone marrow,

are infused into the bloodstream with a drip.

Stem cell transplant involves

transplanting

stem cells, rather than bone marrow cells. Stem cells can be harvested

(collected) from a leukaemia patient's own blood or from a donor. New

alternatives, which are currently experimental, include harvesting stem cells

from umbilical cord blood or placentas of new born babies.

|

SKIN-TUNNELED CATHETER

A

skin-tunneled catheter is a flexible plastic tube passed through the

skin of the chest and inserted into the subclavian vein, which leads to

the heart. It is often used in people who have leukaemia or other

cancers and need to have regular

chemotherapy and

blood tests. Using the catheter, drugs can be injected directly

into the bloodstream and blood samples can be obtained easily. A

skin-tunneled catheter is a flexible plastic tube passed through the

skin of the chest and inserted into the subclavian vein, which leads to

the heart. It is often used in people who have leukaemia or other

cancers and need to have regular

chemotherapy and

blood tests. Using the catheter, drugs can be injected directly

into the bloodstream and blood samples can be obtained easily.

The catheter is inserted under local

anaesthesia and can remain in position for months. The external end is

plugged when not in use. Because the catheter is inserted through the skin

some distance away from the site of entry into the vein, the risk of infection

is reduced.

Using the catheter

The catheter is tunneled under the skin

and enters the subclavian vein to lie with its tip in the heart. A syringe

can be attached to inject drugs.

|

Chronic leukaemia

Treatment for chronic leukaemia depends

on its type and stage. Often treatment is not started unless there are symptoms.

In the early stage, treatment aims to control symptoms by reducing the number of

abnormal cells in the blood.

Biological therapy may be an option for

certain types of leukaemia, such as

chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML).

This involves treatment with

natural substances.

As the condition becomes more advanced,

treatment may consist of mild chemotherapy, blood transfusion and antibiotics

for infections. Some evidence indicates that in chronic myeloid leukaemia, bone

marrow transplantation can prolong life if performed during its chronic phase.

Another available treatment is

monoclonal antibodies. Antibodies are proteins that are produced by certain

cells in response to infection. They usually attach themselves to bacteria or

viruses and help to destroy them. A type of specifically manufactured monoclonal

antibody that recognizes and selectively destroys leukaemia cells can be infused

into the body. An example is alemtuzumab (MabCampath), which is used to treat

chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL).

|

Bone Marrow Transplant

The

choice of treatment and timing of BMT depends on a number of factors including

the patient's age and general health, and the type and stage of the leukaemia.

In a bone marrow transplant, cancerous or abnormal bone marrow is replaced with

healthy marrow. Before the transplant, the recipient's abnormal bone

marrow is eliminated by chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Healthy marrow may

have been supplied by a donor or by the patient when the underlying disease was

inactive. Up to 1 litre (2 pints) of bone marrow may be extracted from the

hipbone with a syringe through a hollow needle. The

choice of treatment and timing of BMT depends on a number of factors including

the patient's age and general health, and the type and stage of the leukaemia.

In a bone marrow transplant, cancerous or abnormal bone marrow is replaced with

healthy marrow. Before the transplant, the recipient's abnormal bone

marrow is eliminated by chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Healthy marrow may

have been supplied by a donor or by the patient when the underlying disease was

inactive. Up to 1 litre (2 pints) of bone marrow may be extracted from the

hipbone with a syringe through a hollow needle.

BMT may be allogenic or autologous. Allogenic BMT requires a donor, often a

relative, whose tissue type is a match for that of the patient. With autologous

BMT some of the patient's own bone marrow is removed, treated with

chemotherapeutic drugs to kill all the abnormal cells and frozen to be used

later.

With both types of BMT the patient receives high doses of chemotherapy and

radiation to destroy their bone marrow and any leukaemic cells in the body. The

donor, or autologous bone marrow, is then injected into the patient. BMT

requires specialized care and support to prevent infection or rejection of the

bone marrow.

Transplantation procedures are

difficult, and side effects are common. They include nausea, vomiting, fatigue,

mouth sores, and loss of appetite. The procedures can also be dangerous and

carry a small risk for death. One of the most serious side effects of both bone

marrow and stem cell transplants is the risk of infection, which can persist for

several months after the transplant. Pneumonia, cytomegalovirus,

aspergillus, and Pneumocystis carini I (a protozoan) are among the

most important life-threatening infections.

|

Dated 19 January 2013

Related Links

|