Small Cell Lung Cancer

Small Cell Lung Cancer

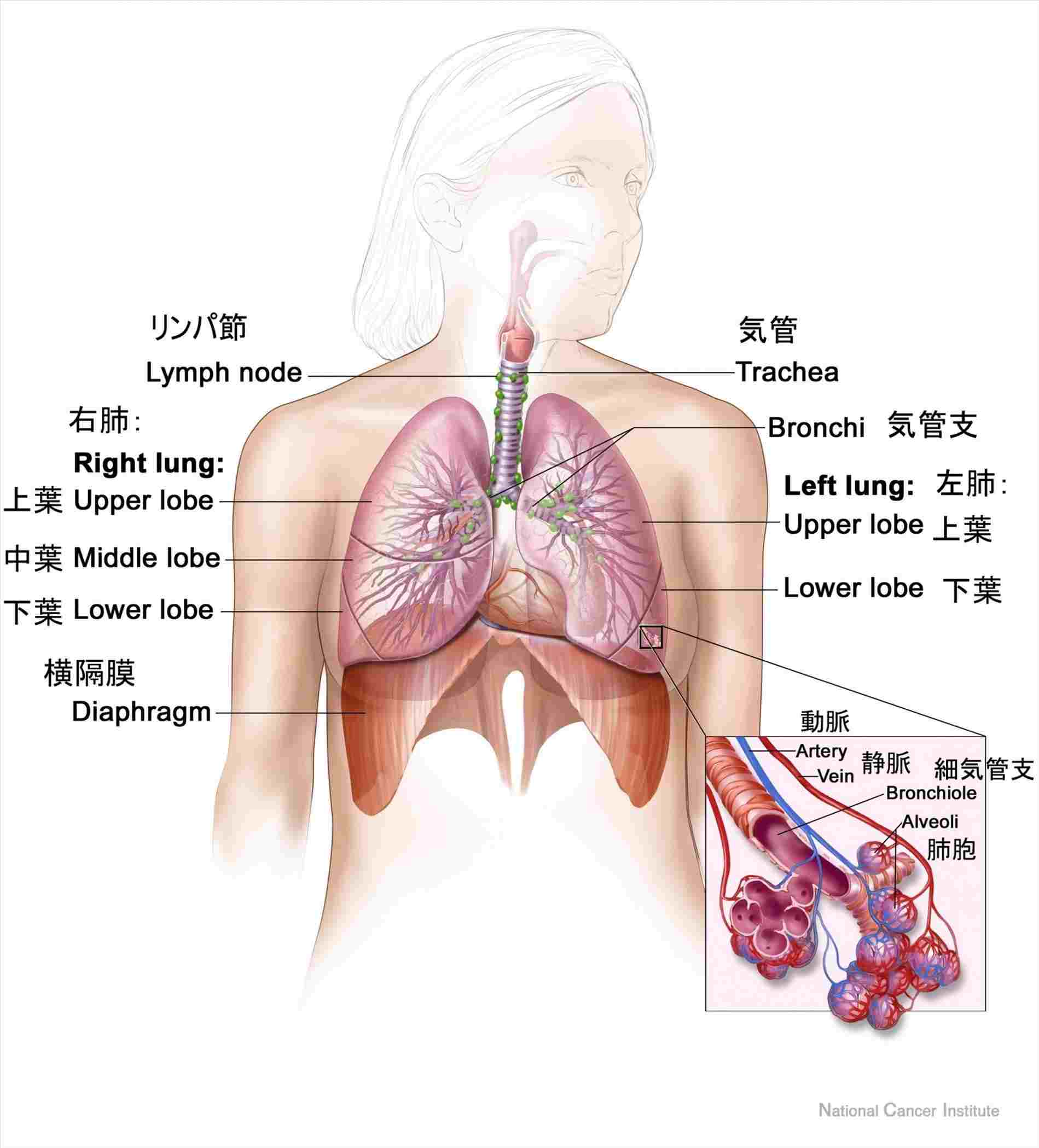

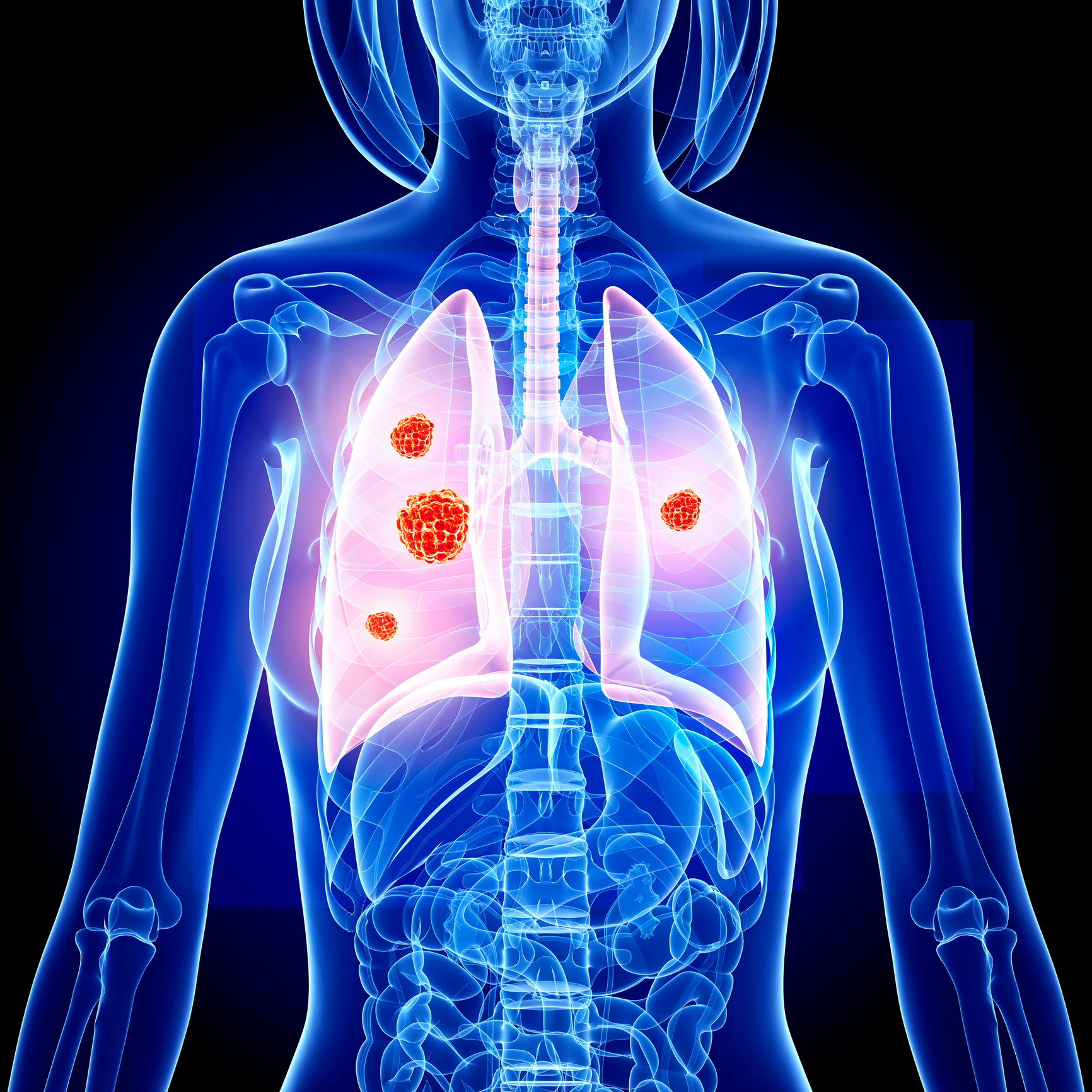

Lung cancer is a deadly disease in which the average survival is 2 to 4 months without treatment, says MedlinePlus. It states that 15 percent of lung cancers are of the small cell type. This type of lung cancer can rapidly spread and create havoc in the body.

Symptoms of small cell lung cancer include shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing up blood, unintentional weight loss and chest pain. This type of lung cancer can also lead to a poor appetite, fever, hoarseness, difficulty swallowing and facial swelling. In some cases, it can lead to weakness and changes in the voice. Small cell lung cancer typically occurs as a result of smoking.

Chemotherapy medications such as etopside, along with radiation treatment may help manage the symptoms of small cell lung cancer but does not cure it. MedlinePlus says that surgery only helps a few people as small cell lung cancer typically spreads by the time it is discovered.

Small-cell carcinoma (sometimes known as “small-cell lung cancer”, or “oat-cell carcinoma”) is a type of highly malignant cancer that most commonly arises within the lung, although it can occasionally arise in other body sites, such as the cervix, prostate, and gastrointesinal tract.

Small-cell carcinoma is an undifferentiated neoplasm composed of primitive-appearing cells.

As the name implies, the cells in small-cell carcinomas are smaller than normal cells, and barely have room for any cytoplasm. Some researchers identify this as a failure in the mechanism that controls the size of the cells.

In a significant number of cases, small-cell carcinomas can produce ectopic hormones, including adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and anti-diuretic hormone (ADH). Ectopic production of large amounts of ADH leads to syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone hypersecretion (SIADH). Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) is a well-known paraneoplastic condition linked to small-cell carcinoma.

Histopathologic image of small-cell carcinoma of the lung. CT-guided core needle biopsy. H&E stain. When associated with the lung, it is sometimes called “oat cell carcinoma” due to the flat cell shape and scanty cytoplasm. It is thought to originate from neuroendocrine cells (APUD cells) in the bronchus called Feyrter cells (named for Friedrich Feyrter). Hence, they express a variety of neuroendocrine markers, and may lead to ectopic production of hormones like ADH and ACTH that may result in paraneoplastic syndromes and Cushing’s syndrome. Approximately half of all individuals diagnosed with Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) will eventually be found to have a small-cell carcinoma of the lung.

Small-cell carcinoma is most often more rapidly and widely metastatic than non-small cell lung carcinoma (and hence staged differently). There is usually early involvement of the hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes.

Combined small-cell lung carcinoma (c-SCLC)

Small-cell lung carcinoma can occur in combination with a wide variety of other histological variants of lung cancer, including extremely complex malignant tissue admixtures. When it is found with one or more differentiated forms of lung cancer, such as squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma, the malignant tumor is then diagnosed and classified as a combined small cell lung carcinoma (c-SCLC). C-SCLC is the only currently recognized subtype of SCLC. Although combined small-cell lung carcinoma is currently staged and treated similarly to “pure” small-cell carcinoma of the lung, recent research suggests surgery might improve outcomes in very early stages of this tumor type.

Smoking is a significant etiological factor.

Symptoms and signs are as for other lung cancers. In addition, because of their neuroendocrine cell origin, small-cell carcinomas will often secrete substances that result in paraneoplastic syndromes such as Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome.

Extrapulmonary small-cell carcinoma

Very rarely, the primary site for small-cell carcinoma is outside of the lungs and pleural space, it is referred to as extrapulmonary small-cell carcinoma (EPSCC). Outside of the respiratory tract, small cell carcinoma can appear in the cervix, prostate, liver, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, or bladder. It is estimated to account for 1,000 new cases a year in the U.S. Histologically similar to small-cell lung cancer, therapies for small-cell lung cancer are usually used to treat EPSCC. First line treatment is usually with cisplatin and etoposide. In Japan, the first line treatment is shifting to irinotecan and cisplatin. When the primary site is in the skin, it is referred to as Merkel cell carcinoma.

Small-cell carcinoma of the prostate

In the prostate, small-cell carcinoma (SCCP) is a rare form of cancer (approx 1% of PC). Due to the fact that there is little variation in prostate specific antigen levels, this form of cancer is normally diagnosed at an advanced stage, after metastasis. It can metastasize to the brain.

Small-cell lung carcinoma has long been divided into two clinicopathological stages, including limited stage (LS) and extensive stage (ES). The stage is generally determined by the presence or absence of metastases, whether or not the tumor appears limited to the thorax, and whether or not the entire tumor burden within the chest can feasibly be encompassed within a single radiotherapy portal. In general, if the tumor is confined to one lung and the lymph nodes close to that lung, the cancer is said to be LS. If the cancer has spread beyond that, it is said to be ES.

In cases of LS-SCLC, combination chemotherapy (often including cyclophosphamide, cisplatinum, doxorubicin, etoposide, vincristine and/or paclitaxel) is administered together with concurrent chest radiotherapy (RT). Chest RT has been shown to improve survival in LS-SCLC.

Exceptionally high objective initial response rates (RR) of between 60% and 90% are seen in LS-SCLC using chemotherapy alone, with between 45% and 75% of individuals showing a “complete response” (CR), which is defined as the disappearance of all radiological and clinical signs of tumor. Unfortunately, relapse is the rule, and median survival is only 18 to 24 months.

Because SCLC usually metastasizes widely very early on in the natural history of the tumor, and because nearly all cases respond dramatically to CT and/or RT, there has been little role for surgery in this disease since the 1970s. However, recent work suggests that in cases of small, asymptomatic, node-negative SCLC’s (“very limited stage”), surgical excision may improve survival when used prior to chemotherapy.(“adjuvant chemotherapy”).

In ES-SCLC, combination chemotherapy is the standard of care, with radiotherapy added only to palliate symptoms such as dyspnea, pain from liver or bone metastases, or for treatment of brain metastases, which, in small-cell lung carcinoma, typically have a rapid, if temporary, response to whole brain radiotherapy.

Combination chemotherapy consists of a wide variety of agents, including cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and carboplatin. Response rates are high even in extensive disease, with between 15% and 30% of subjects having a complete response to combination chemotherapy, and the vast majority having at least some objective response. Responses in ES-SCLC are often of short duration, however.

If complete response to chemotherapy occurs in a subject with SCLC, then prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) is often used in an attempt to prevent the emergence of brain metastases. Although this treatment is often effective, it can cause hair loss and fatigue. Prospective randomized trials with almost two years follow-up have not shown neurocognitive ill-effects. Meta-analyses of randomized trials confirm that PCI provides significant survival benefits. All in all, small-cell carcinoma is very responsive to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and in particular, regimens based on platinum-containing agents. However, most people with the disease relapse, and median survival remains low.

In limited-stage disease, median survival with treatment is 14–20 months, and about 20% of patients with limited-stage small-cell lung carcinoma live 5 years or longer. Because of its predisposition for early metastasis, the prognosis of SCLC is poor with only 10% to 15% of patients surviving 3 years (Washington and Leaver, 2010).

The prognosis is far worse in extensive-stage small-cell lung carcinoma, with treatment, median survival is just 8–13 months, and only 1–5% of patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung carcinoma treated with chemotherapy live 5 years or longer.

Disclaimer

The Content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.