Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a motor neuron disease which causes the weakening and wasting of muscles. Sufferers of this incurable disease eventually lose all control of voluntary movement and some can also develop forms of dementia. Most people with the condition die of pneumonia respiratory failure.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) – also referred to as Motor Neurone Disease (MND) in most Commonwealth countries, and as Lou Gehrig’s disease in the United States– is a debilitating disease with varied etiology characterized by rapidly progressive weakness, muscle atrophy and fasciculations, muscle spasticity, difficulty speaking (dysarthria), difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), and difficulty breathing (dyspnea). ALS is the most common of the five motor neuron diseases.

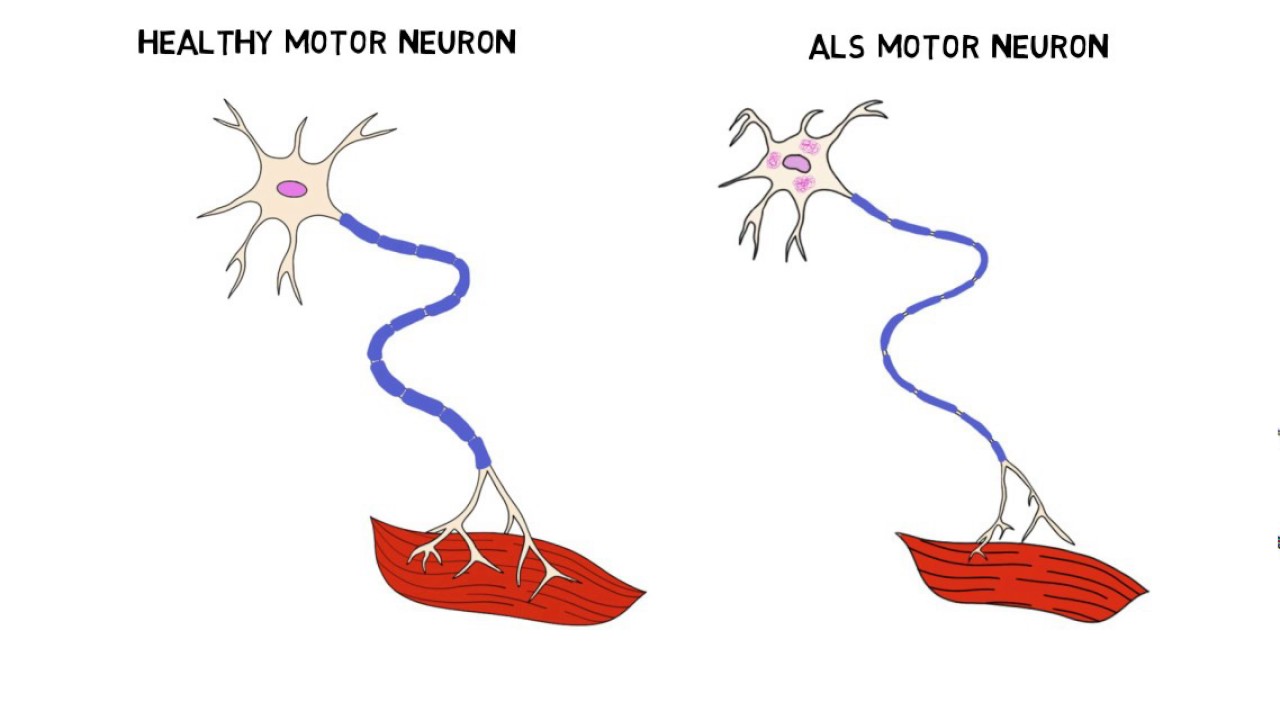

The disorder causes muscle weakness and atrophy throughout the body due to the degeneration of the upper and lower motor neurons. Unable to function, the muscles weaken and atrophy. Individuals affected by the disorder may ultimately lose the ability to initiate and control all voluntary movement, although bladder and bowel sphincters and the muscles responsible for eye movement are usually, but not always, spared until the terminal stages of the disease.

Cognitive function is generally spared for most patients, although some (about 5%) also have frontotemporal dementia. A higher proportion of patients (30–50%) also have more subtle cognitive changes which may go unnoticed, but are revealed by detailed neuropsychological testing. Sensory nerves and the autonomic nervous system are generally unaffected, meaning the majority of people with ALS will maintain hearing, sight, touch, smell, and taste.

There is a known hereditary factor in familial ALS (FALS), where the condition is known to run in families. A defect on chromosome 21, which codes for superoxide dismutase, is associated with approximately 20% of familial cases of ALS, or about 2% of ALS cases overall. This mutation is believed to be transmitted in an autosomal dominant manner, and has over a hundred different forms of mutation. The most common ALS-causing SOD1 mutation in North American patients is A4V, characterized by an exceptionally rapid progression from onset to death. The most common mutation found in Scandinavian countries, D90A, is more slowly progressive than typical ALS and patients with this form of the disease survive for an average of 11 years.

In 2011, a genetic abnormality known as a hexanucleotide repeat was found in a region called C9orf72, which is associated with ALS combined with frontotemporal dementia ALS-FTD, and accounts for some 6% of cases of ALS among white Europeans. The high degree of mutations found in patients that appeared to have “sporadic” disease, (i.e., without a family history) suggests that genetics may play a more significant role than previously thought and that environmental exposures may be less relevant.

No test can provide a definite diagnosis of ALS, although the presence of upper and lower motor neuron signs in a single limb is strongly suggestive. Instead, the diagnosis of ALS is primarily based on the symptoms and signs the physician observes in the patient and a series of tests to rule out other diseases. Physicians obtain the patient’s full medical history and usually conduct a neurologic examination at regular intervals to assess whether symptoms such as muscle weakness, atrophy of muscles, hyperreflexia, and spasticity are getting progressively worse.

Because symptoms of ALS can be similar to those of a wide variety of other, more treatable diseases or disorders, appropriate tests must be conducted to exclude the possibility of other conditions. One of these tests is electromyography (EMG), a special recording technique that detects electrical activity in muscles. Certain EMG findings can support the diagnosis of ALS. Another common test measures nerve conduction velocity (NCV). Specific abnormalities in the NCV results may suggest, for example, that the patient has a form of peripheral neuropathy (damage to peripheral nerves) or myopathy (muscle disease) rather than ALS. The physician may order magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a noninvasive procedure that uses a magnetic field and radio waves to take detailed images of the brain and spinal cord. Although these MRI scans are often normal in patients with ALS, they can reveal evidence of other problems that may be causing the symptoms, such as a spinal cord tumor, multiple sclerosis, a herniated disk in the neck, syringomyelia, or cervical spondylosis.

Based on the patient’s symptoms and findings from the examination and from these tests, the physician may order tests on blood and urine samples to eliminate the possibility of other diseases as well as routine laboratory tests. In some cases, for example, if a physician suspects that the patient may have a myopathy rather than ALS, a muscle biopsy may be performed.

Infectious diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human T-cell leukaemia virus (HTLV), Lyme disease, syphilis and tick-borne encephalitis viruses can in some cases cause ALS-like symptoms. Neurological disorders such as multiple sclerosis, post-polio syndrome, multifocal motor neuropathy, CIDP, spinal muscular atrophy and spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA)can also mimic certain facets of the disease and should be considered by physicians attempting to make a diagnosis.

ALS must be differentiated from the “ALS mimic syndromes” which are unrelated disorders that may have a similar presentation and clinical features to ALS or its variants. Because of the prognosis carried by this diagnosis and the variety of diseases or disorders that can resemble ALS in the early stages of the disease, patients should always obtain a specialist neurological opinion, so that alternative diagnoses are clinically ruled out.

However, most cases of ALS are readily diagnosed and the error rate of diagnosis in large ALS clinics is less than 10%.n one study, 190 patients who met the MND / ALS diagnostic criteria, complemented with laboratory research in compliance with both research protocols and regular monitoring. Thirty of these patients (16%) had their diagnosis completely changed, during the clinical observation development period. In the same study, three patients had a false negative diagnoses, myasthenia gravis (MG), an auto-immune disease. MG can mimic ALS and other neurological disorders leading to a delay in diagnosis and treatment. MG is eminently treatable; ALS is not. Myasthenic syndrome, also known as Lambert-Eaton syndrome (LES), can mimic ALS and its initial presentation can be similar to that of MG. Current research focuses on abnormalities of neuronal cell metabolism involving glutamate and the role of potential neurotoxins and neurotrophic factors.

Slowing progression

Riluzole (Rilutek) is the only treatment that has been found to improve survival but only to a modest extent. It lengthens survival by several months, and may have a greater survival benefit for those with a bulbar onset. It also extends the time before a person needs ventilation support. Riluzole does not reverse the damage already done to motor neurons, and people taking it must be monitored for liver damage (occurring in ~10% of people taking the drug). It is approved by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and recommended by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE).

Disease management

Other treatments for ALS are designed to relieve symptoms and improve the quality of life for patients. This supportive care is best provided by multidisciplinary teams of health care professionals working with patients and caregivers to keep patients as mobile and comfortable as possible.

Pharmaceutical treatments

Medical professionals can prescribe medications to help reduce fatigue, ease muscle cramps, control spasticity, and reduce excess saliva and phlegm. Drugs also are available to help patients with pain, depression, sleep disturbances, dysphagia, and constipation. Baclofen and diazepam are often prescribed to control the spasticity caused by ALS, and trihexyphenidyl or amitriptyline may be prescribed when ALS patients begin having trouble swallowing their saliva.

Physical, occupational and speech therapy

Physical therapists and occupational therapists play a large role in rehabilitation for individuals with ALS. Specifically, physical and occupational therapists can set goals and promote benefits for individuals with ALS by delaying loss of strength, maintaining endurance, limiting pain, preventing complications, and promoting functional independence. Occupational therapy and special equipment such as assistive technology can also enhance patients’ independence and safety throughout the course of ALS. Gentle, low-impact aerobic exercise such as performing activities of daily living (ADL’s), walking, swimming, and stationary bicycling can strengthen unaffected muscles, improve cardiovascular health, and help patients fight fatigue and depression. Range of motion and stretching exercises can help prevent painful spasticity and shortening (contracture) of muscles. Physical and occupational therapists can recommend exercises that provide these benefits without overworking muscles. They can suggest devices such as ramps, braces, walkers, bathroom equipment (shower chairs, toilet risers, etc.) and wheelchairs that help patients remain mobile. Occupational therapists can provide or recommend equipment and adaptations to enable people to retain as much safety and independence in activities of daily living as possible.

ALS patients who have difficulty speaking may benefit from working with a speech-language pathologist. These health professionals can teach patients adaptive strategies such as techniques to help them speak louder and more clearly. As ALS progresses, speech-language pathologists can recommend the use of augmentative and alternative communication such as voice amplifiers, speech-generating devices (or voice output communication devices) and/or low tech communication techniques such as alphabet boards or yes/no signals.

Feeding and nutrition

Patients and caregivers can learn from speech-language pathologists and nutritionists how to plan and prepare numerous small meals throughout the day that provide enough calories, fiber, and fluid and how to avoid foods that are difficult to swallow. Patients may begin using suction devices to remove excess fluids or saliva and prevent choking. Occupational therapists can assist with recommendations for adaptive equipment to ease the physical task of self-feeding and/or make food choice recommendations that are more conducive to their unique deficits and abilities. When patients can no longer get enough nourishment from eating, doctors may advise inserting a feeding tube into the stomach. The use of a feeding tube also reduces the risk of choking and pneumonia that can result from inhaling liquids into the lungs. The tube is not painful and does not prevent patients from eating food orally if they wish.

Researchers have stated that “ALS patients have a chronically deficient intake of energy and recommended augmentation of energy intake.” Both animal and human research suggest that ALS patients should be encouraged to consume as many calories as possible and not to restrict their calorie intake.

Breathing support

When the muscles that assist in breathing weaken, use of ventilatory assistance (intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV), bilevel positive airway pressure (BIPAP), or biphasic cuirass ventilation (BCV)) may be used to aid breathing. Such devices artificially inflate the patient’s lungs from various external sources that are applied directly to the face or body. When muscles are no longer able to maintain oxygen and carbon dioxide levels, these devices may be used full-time. BCV has the added advantage of being able to assist in clearing secretions by using high-frequency oscillations followed by several positive expiratory breaths. Patients may eventually consider forms of mechanical ventilation (respirators) in which a machine inflates and deflates the lungs. To be effective, this may require a tube that passes from the nose or mouth to the windpipe (trachea) and for long-term use, an operation such as a tracheotomy, in which a plastic breathing tube is inserted directly in the patient’s windpipe through an opening in the neck.

Patients and their families should consider several factors when deciding whether and when to use one of these options. Ventilation devices differ in their effect on the patient’s quality of life and in cost. Although ventilation support can ease problems with breathing and prolong survival, it does not affect the progression of ALS. Patients need to be fully informed about these considerations and the long-term effects of life without movement before they make decisions about ventilation support. Some patients under long-term tracheotomy intermittent positive pressure ventilation with deflated cuffs or cuffless tracheotomy tubes (leak ventilation) are able to speak, provided their bulbar muscles are strong enough. This technique preserves speech in some patients with long-term mechanical ventilation. Other patients may be able to utilize a speaking valve such as a Passey-Muir Speaking Valve with the assistance and guidance of a speech-language pathologist.

Palliative care

Social workers and home care and hospice nurses help patients, families, and caregivers with the medical, emotional, and financial challenges of coping with ALS, particularly during the final stages of the disease. Social workers provide support such as assistance in obtaining financial aid, arranging durable power of attorney, preparing a living will, and finding support groups for patients and caregivers. Home nurses are available not only to provide medical care but also to teach caregivers about tasks such as maintaining respirators, giving feedings, and moving patients to avoid painful skin problems and contractures. Home hospice nurses work in consultation with physicians to ensure proper medication, pain control, and other care affecting the quality of life of patients who wish to remain at home. The home hospice team can also counsel patients and caregivers about end-of-life issues.

Disclaimer

The Content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.