Significant improvements in heart shape and function can happen one year after an operation for weight loss

SAN DIEGO (Tuesday, October 24, 5:30 pm PDT): In overweight and obese people, fat often gets deposited in the midsection of the body. Large amounts of this belly fat can lead to unhealthy changes in a heart’s function and size. But according to new findings presented at the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2017, a bariatric surgical procedure, and the weight loss that follows it, actually allows the heart to return to its natural shape and function.

When a person lifts weights, pushing against resistance, their muscles eventually get bigger. The same is true for the heart muscle. When a person is overweight, the heart has to generate more force to pump even more blood throughout the body. This extra workload causes the heart muscle to grow bigger. But contrary to what some people think, a bigger heart muscle doesn’t mean a stronger heart. In fact, the larger the heart, the less efficacious it is at fulfilling its functions.

“We know that obesity is the most prevalent disease in the United States. And that the cardiovascular system is significantly affected by this disease process,” said lead study author Raul J. Rosenthal, MD, FACS, chairman, department of General Surgery at the Cleveland Clinic in Weston, Florida. “But we wanted to know to what degree the shape of the heart changes in someone who is obese, what the heart looks like in someone after having bariatric surgery and losing weight, and how that change in geometry affects heart functionality.”

For this study, researchers at the Cleveland Clinic reviewed data on 51 obese men and women who underwent bariatric surgery between 2010 and 2015. The analysis included factors such as BMI and coexisting health problems. The average age of the patients was 61years and the average body mass index (BMI) was 40, which means that the person is about 100 pounds overweight.

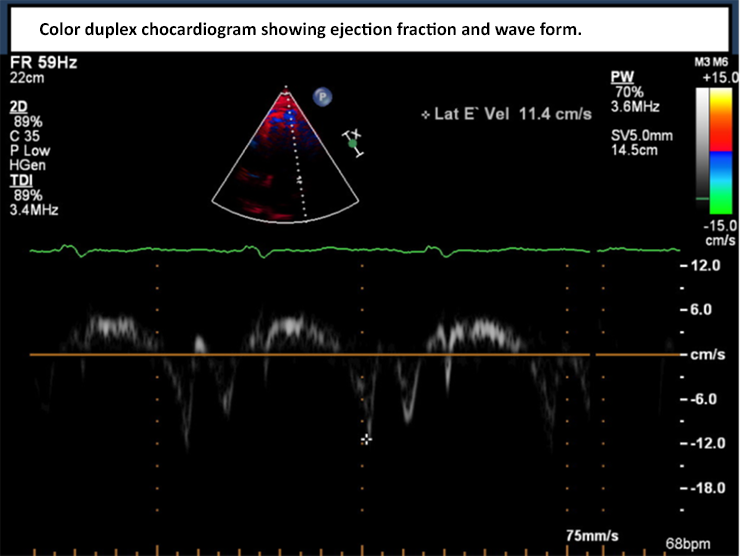

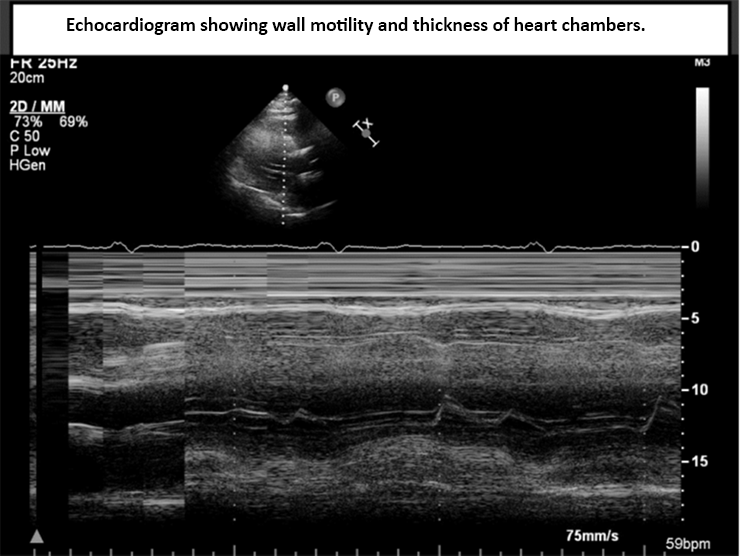

To better understand the impact of a bariatric operation and weight loss on heart health, the researchers compared preoperative and postoperative echocardiography readings. An echocardiogram is an ultrasound of the heart that measures not only its size and geometry, but also its function. An echocardiogram measures how much blood is in the heart, how much blood goes out of the heart, and how much blood remains in the heart.

One year after bariatric surgery, the researchers found significant improvements in patients’ heart health. Nearly half of the patients had hearts that had gone back to their natural shape or geometry. They also found that there was a significant improvement in the size of the ventricles: on average these chambers of the heart decreased in size by 15.7 percent (left ventricle mass: 229 grams before surgery; 193 grams after surgery. Left ventricular wall diameter: 60.1 mm before surgery; 53.7 mm after surgery.)

Larger chambers lose some of their pumping power. This loss means that more blood stays in the heart, and ultimately increases a person’s risk of heart failure.

“When the size of the chambers gets bigger and the walls of the heart get thicker, the blood flow to the heart is not as good, the functionality of the heart is not as good, and the heart itself doesn’t get enough blood,” Dr. Rosenthal said. “The whole body suffers because there is less blood going to your feet and to your toes and to your brain.”

This study is the beginning of a series of studies that will be conducted by these researchers over the next few years. They will perform follow up studies to find out what the window is in which losing weight allows the heart to go back to its normal geometry.

Image A: Echocardiogram showing ejection fraction (EF) of 70 percent. EF is a measurement of the amount of blood being pumped out of the left ventricle (LV), the heart’s main pumping chamber. A LVEF between 55 and 70 percent is considered normal.

Image B: Echocardiogram showing wall motility and thickness of heart chambers.

“We don’t know if being obese for 20 years and having changes in your heart geometry is different from being obese for 10 years,” Dr. Rosenthal said. “The question is: will the heart always come back to normal? It could be if you wait too long, the changes in your heart are irreversible.”

Other study authors, all from Cleveland Clinic Florida, are Rajmohan Rammohan, MD; Nisha Dhanabalsamy; Emanuele Lo Menzo, MD, PhD, FACS; and Samuel Szomstein, MD, FACS.

“FACS” designates that a surgeon is Fellow of the American College of Surgeons.