Colorectal Cancer cancer of the colon or rectum

The colon and the rectum are part of the large

intestine, which is part of the digestive system. Because colon cancer and

rectal cancers have many features in common, they are sometimes referred to

together as colorectal cancer. Colorectal cancer includes cancers of both the

large intestine (colon), the lower part of your digestive system, and the

rectum, the last 8 to 10 inches of the colon.

Most colon and rectal cancers begin as small,

noncancerous (benign) clumps of cells called adenomatous polyps. Over time some

of these polyps become cancerous.

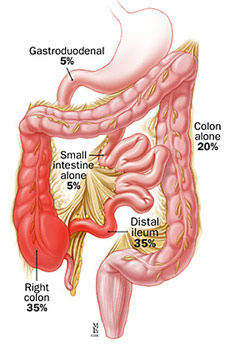

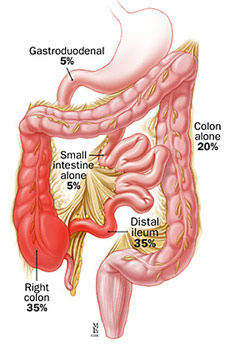

The colon is the first 6 feet of the large intestine. It has four sections:

-

The first section is called the ascending colon. It extends upward on the right

side of the abdomen.

-

The second section is called the transverse colon since it goes across the body

to the left side.

-

There it joins the third section, the descending colon, which continues downward

on the left side.

-

The fourth section is known as the sigmoid colon because of its S-shape. The

sigmoid colon joins the rectum, which, in turn, joins the anus, or the opening

where waste matter passes out of the body.

There are several causes for colorectal cancer as well as factors that place

certain individuals at increased risk for the disease. There are known genetic

and environmental factors.

People at risk for colorectal cancer:

-

The biggest risk factor is age.

Colorectal cancer is rare in those under 40 years. The rate of colorectal

cancer detection begins to increase after age 40. Most colorectal cancer is

diagnosed in those over 60 years.

-

Have a mother, father, sister,

or brother who developed colorectal cancer or polyps. When more than one

family member has had colorectal cancer, the risk to other members may be

three-to-four times higher of developing

the

disease. This higher risk may be due to an inherited gene.

-

Have history of benign

growths, such as polyps, that have been surgically removed.

-

Have a prior history of

colon or rectal cancer.

-

Have disease or condition linked

with increased risk.

-

Have a diet high in

fat and low in

fiber.

Having certain diseases or conditions may place

people at increas ed

risk for colorectal cancer. These include ed

risk for colorectal cancer. These include

-

Chronic

ulcerative colitis, an inflammatory condition of the colon. People in this

risk category have long-term disease, most for ten years or more.

-

Crohn's

disease,

which is an inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal

tract. This disease may increase colorectal cancer risk, although not as much

ulcerative colitis.

-

-

Inherited a specific colorectal

cancer syndrome. Those with an inherited syndromes may develop colorectal

cancer at a much younger age, in their 30s or even younger. Over the past

several years, genetic forms of colorectal cancer have been identified and

genetic tests developed.

Symptoms of

colorectal cancer

The symptoms of colorectal cancer can be confused

with those of a number of digestive disorders. Having one or more of these

symptoms does not mean you have cancer

The following are the most common symptoms of

colorectal cancer. However, each individual may experience symptoms differently.

Women who have any of the following symptoms

should check with their physicians, especially if they are over 40 years old or

have a personal or family history of the disease:

-

A change in bowel habits such as

diarrhea, constipation, or

narrowing of the stool that lasts for more than a few days.

-

Rectal bleeding or blood in the

stool

-

Cramping or gnawing stomach pain

-

Decreased appetite

-

Vomiting

-

Unexplained weight loss,

unusually low red blood cell counts or

anemia, weakness and

fatigue

-

Jaundice (yellowish coloring) of

the skin or sclera of the eye

The symptoms of colorectal cancer may resemble

other conditions, such as infections,

hemorrhoids, and

inflammatory bowel disease. It is also possible to have colon cancer and not

have any symptoms. Always consult your physician for a diagnosis.

Most colon cancers develop from polyps. Screening is extremely important for

detecting polyps before they become cancerous. It can also help find colorectal

cancer in its early stages when you have a good chance for recovery.

The doctor performs a thorough clinical evaluation

that includes:

-

A complete medical, family, and

drug history

-

A physical examination,

including a digital rectal examination

Common screening and diagnostic

procedures include the following:

-

Digital rectal exam. In this office exam, your doctor uses a gloved finger to

check the first few inches of your rectum for large polyps and cancers.

Although safe and painless, the exam is limited to your lower rectum and can't

detect problems with your upper rectum and colon. In addition, it's difficult

for your doctor to feel small polyps.

-

Fecal occult (hidden) blood test. This test checks a

sample of your stool for blood. It can be performed in your doctor's office,

but you're usually given a kit that explains how to take the sample at home.

You then return the sample to a lab or your doctor's office to be checked. The

problem is that not all cancers bleed, and those that do often bleed

intermittently. Furthermore, most polyps don't bleed. This can result in a

negative test result, even though you may have cancer. On the other hand, if

blood shows up in your stool, it may be the result of hemorrhoids or an

intestinal condition other than cancer. For these reasons, many doctors

recommend other screening methods instead of, or in addition to, fecal occult

blood tests. Fecal occult (hidden) blood test. This test checks a

sample of your stool for blood. It can be performed in your doctor's office,

but you're usually given a kit that explains how to take the sample at home.

You then return the sample to a lab or your doctor's office to be checked. The

problem is that not all cancers bleed, and those that do often bleed

intermittently. Furthermore, most polyps don't bleed. This can result in a

negative test result, even though you may have cancer. On the other hand, if

blood shows up in your stool, it may be the result of hemorrhoids or an

intestinal condition other than cancer. For these reasons, many doctors

recommend other screening methods instead of, or in addition to, fecal occult

blood tests.

-

Flexible sigmoidoscopy.

In this test, your doctor uses a

flexible, slender and lighted tube to examine your rectum and sigmoid

approximately the last 2 feet of your colon. Nearly half of all colon cancers

occur in this area. The test usually takes just a few minutes. It can

sometimes be somewhat uncomfortable, and there's a slight risk of perforating

the colon wall.

-

Barium enema. This diagnostic test allows your doctor to

evaluate your entire large intestine with an X-ray. Barium, a contrast dye, is

placed into your bowel in an enema form. During a double contrast barium

enema, air is also added. The barium fills and coats the lining of the bowel,

creating a clear silhouette of your rectum, colon and sometimes a small

portion of your small intestine. This test typically takes about 20 minutes

and can be somewhat uncomfortable. There's also a slight risk of perforating

the colon wall. A flexible sigmoidoscopy is often done in addition to the

barium enema to aid in detecting small polyps that a barium enema X-ray may

miss, especially in the lower bowel and rectum.

-

Colonoscopy.

This procedure is the most sensitive test for

colorectal cancer and polyps. Colonoscopy is similar to flexible sigmoidoscopy,

but the instrument used a colonoscope, which is a long, flexible and slender

tube attached to a video camera and monitor allows your doctor to view your

entire colon and rectum. If any polyps are found during the exam, your doctor

may remove them immediately or take tissue samples (biopsies) for analysis.

This is done through the colonoscope and is painless. If you have adenomatous

polyps, especially those larger than 5 millimeters in diameter, you'll need

careful screening in the future.

A colonoscopy takes about a half-hour. You may

receive a mild sedative to make you more comfortable. Preparation for the

procedure involves drinking a large amount of fluid containing a laxative to

clean out your colon enemas are no longer necessary. Major risks of

diagnostic colonoscopy include hemorrhage and perforation of the colon wall.

But these risks are rare. Complications may be somewhat more frequent when

polyps are removed.

-

Genetic testing. If you have a family history of colorectal cancer, you

may be a candidate for genetic testing. This blood test may help determine if

you're at increased risk of colon or rectal cancer, but it's not without

drawbacks. The results can be ambiguous, and the presence of a defective gene

doesn't necessarily mean you'll develop cancer. Knowing you have a genetic

predisposition can alert you to the need for regular screening. Still, you'll

also want to consider the psychological impact of what the test may reveal.

Knowing you may develop cancer affects not only your own life, but the lives

of everyone close to you. Genetic testing for children is even more complex

and problematic. It's best if you discuss all of the ramifications of genetic

testing with your doctor or a medical geneticist.

Another new test checks a stool sample for DNA

from abnormal cells. In preliminary studies, the test has proved to be so

accurate it may eventually eliminate the need for more-invasive examinations

such as colonoscopy, at least in average-risk circumstances. A three-year

clinical trial of this test by the National Cancer Institute is under way.

Screening Guidelines for Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer screening guidelines

from the American Cancer Society for early detection include:

-

Beginning at age 50,

both men and women should follow this testing schedule: Digital rectal

examination should be performed at the time of each screening

sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, or barium enema examination.

-

Yearly fecal occult

blood test, plus:

-

flexible sigmoidoscopy

every 5 years, or

-

colonoscopy every 10

years, or

-

double contrast barium

enema every 5-10 years

-

People with any of the

following colorectal cancer risk factors should begin screening

procedures at an earlier age:

-

strong family history of

colorectal cancer or polyps (cancer or polyps in a first degree

relative younger than 60 or in two first degree relatives of any age)

-

family with hereditary

colorectal cancer syndromes (familial adenomatous polyposis and

hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer)

-

personal history of

colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps

-

|

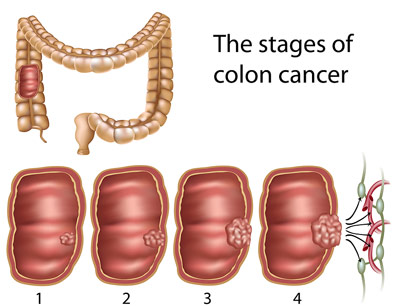

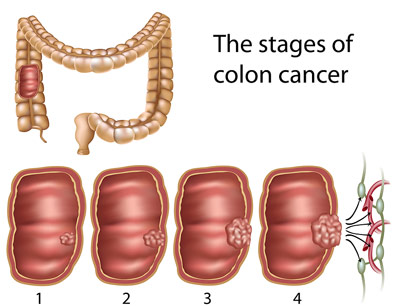

Staging of

Colorectal Cancer

Staging is the process of finding out how far the cancer has spread. This is

very important because your treatment and the outlook for your recovery depend

on the stage of your cancer. For early cancer, surgery may be all that is

needed. For more advanced cancer, other treatments such as chemotherapy or

radiation therapy may be used.

Stage 0

For cancers that are stage 0, the disease has

not grown beyond the lining of the colon or rectum. Therefore surgical removal

or destruction of the cancer is all that is needed. For larger tumors, a rectal

or colon resection may be required.

Stage 1

For

colon cancer, Stage 1 cancers have grown through several layers of the colon but

have not spread outside the colon itself. Standard treatment is a colon

resection with no other treatment generally needed.

Like colon cancer, Stage 1 rectal cancers have

grown through numerous layers of tissue but not outside the rectum. The type of

surgery used to treat this is dependant upon the location of the cancer, but the

primary treatment is an abdominoperineal resection. Chemotherapy and radiation

are sometimes administered before or after surgery.

Stage 2

Stage 2 colon cancer has penetrated the wall

of the colon and spread into nearby tissue. However, it has not yet reached the

lymph nodes. Usually the only treatment for this stage is a resection. Since

some Stage 2 colon cancers have a tendency to recur, the doctor may also decide

to treat the patient with chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Once rectal cancer has reached Stage 2, it too has

penetrated the walls of the rectum but has not yet reached the lymph nodes. It

is generally treated with a resection and then both chemotherapy and radiation

therapy.

Stage 3

Stage 3 is considered an advanced stage of

colorectal cancer. The disease has spread to the lymph nodes, but not to other

parts or organs in the body. For both colon and rectal cancer, sectional surgery

is done first and is followed by chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

Stage 4

For patients with Stage 4 colorectal cancer,

the disease has spread to distant organs such as the liver, lungs and ovaries.

When the cancer has reached this stage, surgery is generally aimed at relieving

or preventing complications as opposed to curing the patient of the disease.

Occasionally the cancers spread is restricted enough to where it can all be

removed by surgery. For Stage 4 cancer that cannot be surgically removed,

chemotherapy, radiation therapy or both may be used to alleviate, delay or

prevent symptoms

Treatment

for colorectal cancer

Specific treatment for colorectal cancer will be

determined by your physician based on:

-

your age, overall health, and

medical history

-

extent of

the disease

-

your tolerance for specific

medications, procedures, or therapies

-

expectations for the course of

the disease

-

your opinion or preference

Treatment choices for the person with colon cancer

depend on the stage of the tumor - if it has spread and how far. When the

disease has been found and staged, your physician will suggest a treatment plan.

Treatment may include:

-

Colon surgery

Often, the primary treatment for colorectal cancer is an

operation called a segmental resection, in which the cancer and a length of

normal tissue on either side of the cancer are removed, as well as the nearby

lymph nodes.

-

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy radiation to

kill cancer cells either after surgery, to kill small areas of cancer that may

not be seen during surgery, or instead of surgery. Radiation may also be used

to ease (palliate) symptoms such as pain, bleeding, or blockage. There are two

ways to deliver radiation therapy, including the following:

-

External beam

radiation

External beam radiation uses radiation from

outside the body, which is focused on the cancer.

-

Internal

radiation therapy

Internal radiation therapy uses small pellets of

radioactive material placed directly into the cancer.

-

Chemotherapy

Drugs (medications) are given into a vein or by

mouth to kill

cancer cells throughout the body. Studies have shown that chemotherapy after

surgery can increase the survival rate for patients with some stages of colon

cancer. Chemotherapy can also help relieve symptoms of advanced cancer.

Dated 14th March, 2005

Related Links

|

ed

risk for colorectal cancer. These include

ed

risk for colorectal cancer. These include  Fecal occult (hidden) blood test. This test checks a

sample of your stool for blood. It can be performed in your doctor's office,

but you're usually given a kit that explains how to take the sample at home.

You then return the sample to a lab or your doctor's office to be checked. The

problem is that not all cancers bleed, and those that do often bleed

intermittently. Furthermore, most polyps don't bleed. This can result in a

negative test result, even though you may have cancer. On the other hand, if

blood shows up in your stool, it may be the result of hemorrhoids or an

intestinal condition other than cancer. For these reasons, many doctors

recommend other screening methods instead of, or in addition to, fecal occult

blood tests.

Fecal occult (hidden) blood test. This test checks a

sample of your stool for blood. It can be performed in your doctor's office,

but you're usually given a kit that explains how to take the sample at home.

You then return the sample to a lab or your doctor's office to be checked. The

problem is that not all cancers bleed, and those that do often bleed

intermittently. Furthermore, most polyps don't bleed. This can result in a

negative test result, even though you may have cancer. On the other hand, if

blood shows up in your stool, it may be the result of hemorrhoids or an

intestinal condition other than cancer. For these reasons, many doctors

recommend other screening methods instead of, or in addition to, fecal occult

blood tests.