Kidney stones are increasing, particularly among adolescents, females, and African-Americans in the U.S., a striking change from the historic pattern in which middle-aged white men were at highest risk for the painful condition.

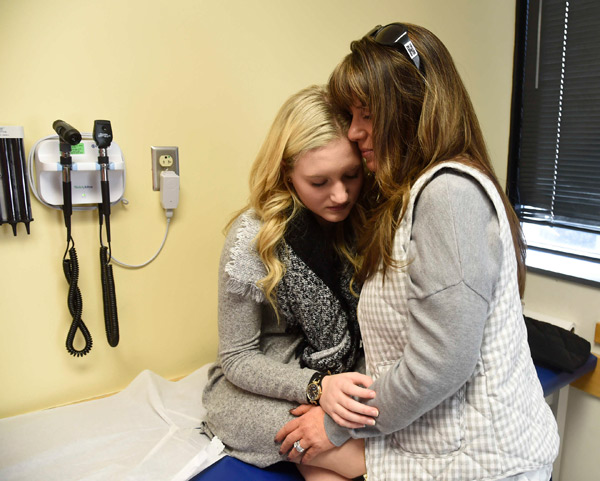

“The emergence of kidney stones in children is particularly worrisome, because there is limited evidence on how to best treat children for this condition,” said study leader Gregory E. Tasian, M.D., M.Sc., M.S.C.E., a pediatric urologist and epidemiologist at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). “The fact that stones were once rare and are now increasingly common could contribute to the inappropriate use of diagnostic tests such as CT scans for children with kidney stones, since health care providers historically have not been accustomed to evaluating and treating children with kidney stones.”

Tasian added, “These trends of increased frequency of kidney stones among adolescents, particularly females, are also concerning when you consider that kidney stones are associated with a higher risk of chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular and bone disease, particularly among young women.”

The research by Tasian and colleagues appeared online in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

Researchers, clinicians and public health experts have been aware of the overall increase in kidney stones in children and adolescents, but the current study provided greater clarity on the specific groups of patients at greatest risk by analyzing age, race and sex characteristics among children and adults in South Carolina over a 16-year period, from 1997 to 2012.

Drawing on state medical records, the study team analyzed data from nearly 153,000 child and adult kidney stone patients from a total population of 4.6 million. Overall, the annual incidence of kidney stones increased 16 percent between 1997 and 2012. The greatest rates of increase were among adolescents (4.7 percent per year), females (3 percent per year), and African-Americans (2.9 percent per year). Between 1997 and 2012 the risk of kidney stones doubled during childhood for both boys and girls, while there was a 45 percent increase in the lifetime risk for women.

The highest rate of increase in kidney stones was among adolescent females, and in any given year, stones were more common among females than males aged 10 to 24 years. After age 25, kidney stones became more common among men.

Among African-Americans, the incidence of kidney stone increased 15 percent more than in whites within each five-year period covered by the study.

Possible factors for the rise in kidney stones, said the authors, may include poor water intake and dietary habits, such as an increase in sodium and a decrease in calcium intake. However, the current study did not examine dietary differences. In addition, dehydration, which promotes the growth of kidney stones, is related to both poor water intake and higher temperatures. Tasian led a 2014 study that showed a link between higher daily temperatures and an increase in patients seeking treatment for kidney stones in five U.S. cities, a link that may be a consequence of climate change.

Tasian added that the age, sex and race differences that his team found among kidney stone patients will require further study, but that the patterns they found may assist physicians and public health officials in designing targeted prevention strategies for people at higher risk for the condition.

The above post is reprinted from materials provided by Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.