The expert report underpinning the latest dietary guidelines for Americans fails to reflect much relevant scientific literature in its reviews of crucial topics and therefore risks giving a misleading picture, an investigation by The BMJ has found.

Concern about the report has prompted the US Congress to schedule a hearing on the guidelines in October, when two cabinet secretaries are scheduled to testify, writes journalist Nina Teicholz in an article published today.

The guidelines will affect the diet of tens of millions of American citizens, as well as food labelling, education and research priorities. In the past, most Western nations have adopted similar dietary advice. They are based on a report produced by an advisory committee — a group of 14 experts appointed to review the best and most current science to make nutrition recommendations that both promote health and fight disease.

The previous committee in 2010 made an effort to bring greater scientific rigor to the process by using the Nutrition Evidence Library (NEL), set up by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), to help conduct reviews.

But the 2015 committee has not used NEL methods for the majority of its analyses, notes Teicholz. Instead it relies heavily on systematic reviews from professional bodies, such as the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology, who are supported by food and drug companies.

The committee members, who are not required to list their potential conflicts of interest, also conducted ‘ad hoc’ reviews of the literature, without any systematic criteria for how studies were identified, selected, or evaluated, she adds.

On saturated fats, for example, the committee did not conduct a formal review of the literature from the past five years, even though several prominent papers published since 2010 failed to confirm any association between saturated fats and heart disease. Despite a great deal of conflicting evidence over the past five years, the committee’s report concludes that the evidence linking consumption of saturated fats to cardiovascular disease is “strong.”

On the effectiveness of low carbohydrate diets, again, the committee did not request a NEL systematic literature review from the past five years, writes Teicholz. Yet dozens of randomised controlled clinical trials published since 2000 show that low carbohydrate diets are at least equal to if not better than other nutritional approaches for controlling type 2 diabetes, achieving weight loss in the short term, and improving most heart disease risk factors.

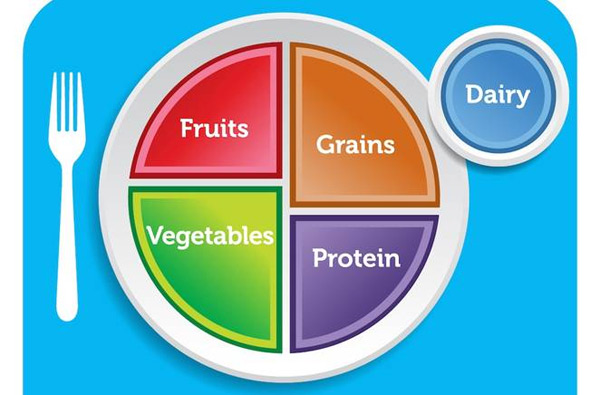

“Given the growing toll taken by these conditions and the failure of existing strategies to make meaningful progress in fighting obesity and diabetes to date, one might expect the guideline committee to welcome any new, promising dietary strategies,” says Teicholz. Yet the committee largely sticks to the same advice it has given for decades — to eat less saturated fat (in meat and full-fat dairy products) and more plant foods for good health.

Abandoning established review methods “opens the door not only to potential bias but also for the possibility of influence from outside agendas and commercial interests, and all of these can be observed in the report,” she observes. The prevailing bias, she adds, appears to be one to preserve the nutrition recommendations of the past 35 years.

Nevertheless, the report is highly confident that its findings are supported by good science.

Committee chair, Barbara Millen told The BMJ: “On topics where there were existing comprehensive guidelines, we didn’t do them. We used those resources and that time to cover other questions,” she explained. “That’s why you have an expert committee . . . to bring expertise,” including “our own original analyses.”

On saturated fats, Millen said that her committee had “worked with the NEL and USDA assistance to identify the research literature.” And on low carbohydrate diets, she said that there was “not substantial evidence” to consider. “Many popular diets don’t have evidence. But can you achieve healthiness, the answer is yes.”

Regarding the committee’s conflicts of interest, she said that members were vetted by counsel to the federal government.

Yet given the ever increasing toll of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, and the failure of existing strategies to make inroads in fighting these diseases, there is an urgent need to provide nutritional advice based on sound science, argues Teicholz.

“It may be time to ask our authorities to convene a fresh, truly independent panel of scientists free from potential conflicts to undertake a comprehensive review, in order to ensure that selection of the dietary guidelines committee becomes more transparent, and that the most rigorous scientific evidence is reliably used to produce the best possible nutrition policy,” she concludes.

Dr Fiona Godlee, The BMJ’s Editor in Chief adds: “These guidelines are hugely influential, affecting diets and health around the world. The least we would expect is that they be based on the best available science. Instead the committee has abandoned standard methodology, leaving us with the same dietary advice as before — low fat, high carbs.

Growing evidence suggests that this advice is driving rather than solving the current epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes. The committee’s conflicts of interest are also a concern. We urgently need an independent review of the evidence and new thinking about diet and its role in public health.”