What if you could zap your hunger away? A device approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on Wednesday promises to do just that.

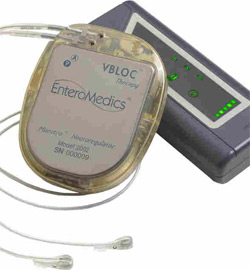

The VBLOC vagal blocking device, developed by EnteroMedics of St. Paul, Minn., generates an electrical pulse in the vagus nerve, perhaps blocking communication between the brain and stomach. Normally, the nerve helps tell the brain whether the stomach is empty or full, among many other tasks.

“I suspect it blinds the brain of what’s going on in the gastrointestinal tract,” says Dr. Scott Shikora, director of the Center for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and consulting chief medical officer to EnteroMedics. However, researchers don’t really know why stimulating the vagus nerve might make people feel less hungry.

“A lot of the interest in the vagus nerve as an avenue to promote weight loss stems from animal studies that found that stimulating the vagus nerve close to the stomach resulted in weight loss and decreased eating,” psychologist Jamie Bodenlos at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, who is unaffiliated with the device, told Shots via email.

Zapping the vagus nerve is not a new therapy. Vagus nerve stimulation has been approved by the FDA to treat chronic or recurrent depression that doesn’t respond to treatment, as well as epilepsy. It also can be used for patients with gasteroparesis, a condition when the stomach doesn’t empty completely.

But VNS is not considered a first-line solution for those disorders, and it won’t be for obesity, either.

This device won’t be for most people who need to lose weight. It’s only approved for patients over 18 who have unsuccessfully tried a weight loss program, have a body mass index of 35 to 45 and have an additional obesity-related illness like Type 2 diabetes.

The system includes three implanted devices. There’s a pulse generator that sends electrical impulses, placed in the upper left chest, and two lead wires that are placed on the vagus nerve in the abdomen. Outside the body, the signals can be modified by a controller that attaches to a battery charger and a transmitter coil.

In a clinical trial, published in the September 2014 issue of JAMA, the journal of the American Medical Association, 233 patients in Australia and the United States with a BMI of 35 or greater used the device for 18 months. Some had it turned on, while others had the device implanted but inactive.

The participants had an average BMI of 41, which means a person who is 5 foot 8 would weigh 270 pounds. They were considered about 97 pounds overweight on average.

After 12 months, the group using an active device had lost about 24 percent of that excess weight, or 9 percent of their total body weight. That’s compared to the people with the sham devices, who lost 16 percent of excess weight, or about 6 percent of body weight. The people who had the sham devices probably lost weight because of the placebo effect, the researchers speculate, and also because all of the people in the study were participating in a diet and exercise program.

A lap band displayed on a model of a human stomach. It creates a small pouch at the top of the stomach that makes people feel full more quickly.

The people using the active devices did say they were less hungry. About 4 percent of people reported serious adverse events, including surgical complications, pain at the electrode sites, heartburn, and abdominal pain.

Although the device didn’t help people lose 10 percent more excess weight, than the control group, which was the study’s target, the FDA Advisory Committee on Gastroenterology-Urology Devices found that the benefits were still significant enough to approve the device for patients meeting certain criteria.

Researchers not involved with the device caution that the results show only moderate weight loss and shouldn’t be overstated.

“It is possible that this will be a component of treatment of obesity, but it’s too early to tell,” says Dr. Dario Englot, a neurosurgeon at the University of California San Francisco who has studied vagus nerve stimulation for epilepsy. “It’s also possible that the effects that have been seen are the result of coincidence and this is going to be a fad that falls by the wayside.”

However, Englot says, “Because obesity is such a problem, I think it’s a positive step to try new treatments as long as we know that they’re safe, and we know now that this is relatively safe.”

The FDA hadn’t approved an obesity device since September 2007, when the Realize gastric band was approved for bariatric surgery.

The FDA has ordered EnteroMedics to follow at least 100 additional patients over the next five years to collect safety and effectiveness data on weight loss and side effects with the device.

According to the company, they’re working on getting insurance coverage for the device. They say pricing will be comparable to other bariatric procedures, in the $10,000 to $30,000 range.

But, says Englot, the best tool against obesity “continues to be a diet and exercise regime and no surgical procedure or device is going to replace that.”